17 Combining Datasets

17.1 Introduction: Why Combine Datasets?

In real-world data analysis, information is rarely contained in a single dataset. You’ll often need to combine multiple datasets from different sources to get a complete picture. This process is fundamental to data analysis and goes by several names:

- Merging - joining datasets based on common keys

- Joining - combining datasets using indices

- Concatenating - stacking datasets vertically or horizontally

17.1.1 Common Scenarios Requiring Data Combination

1. Distributed Information

- Customer demographics in one table, purchase history in another

- Product details separate from sales transactions

- Survey responses split across multiple files

2. Data from Multiple Sources

- Internal company data + external market data

- Multiple databases (HR, Sales, Inventory)

- Different time periods stored in separate files

3. Analytical Requirements

- Enriching existing data with additional attributes

- Comparing data across different groups or time periods

- Building comprehensive datasets for machine learning

17.1.2 The Three Main Combination Methods

Pandas provides three powerful functions for combining datasets, each suited to different scenarios:

| Method | Function | Use Case | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Merge | merge() |

Combine datasets with common columns (like SQL JOIN) | on= (column name) |

| Join | join() |

Combine datasets using their indices | lsuffix=, rsuffix= |

| Concatenate | concat() |

Stack datasets vertically or horizontally | axis= (0 or 1) |

In this chapter, we’ll explore each method with practical examples, understand when to use which approach, and learn how to handle common challenges like missing values and duplicate columns.

17.1.3 Setup: Loading Required Libraries

Let’s start by importing the necessary libraries and loading our example datasets.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Display settings for better output

pd.set_option('display.max_columns', None)

pd.set_option('display.width', None)17.2 Method 1: Merging with merge()

The merge() function is pandas’ most versatile tool for combining datasets. It works similarly to SQL JOIN operations, combining DataFrames based on one or more common columns (called keys).

17.2.1 Basic Syntax

pd.merge(left_df, right_df, on='key_column', how='inner')Or using the DataFrame method:

left_df.merge(right_df, on='key_column', how='inner')Let’s see this in action!

17.2.2 Example Datasets: Lord of the Rings Fellowship

Throughout this chapter, we’ll use multiple datasets that contain complementary information, we’ll combine using different methods.

Let’s first load the primary dataset containing basic fellowship member information:

# Load the primary dataset

df_existing = pd.read_csv('./datasets/LOTR.csv')

print(f"Dataset shape: {df_existing.shape}")

print(f"Columns: {list(df_existing.columns)}\n")

df_existing.head()Dataset shape: (4, 3)

Columns: ['FellowshipID', 'FirstName', 'Skills']

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening |

| 2 | 1003 | Gandalf | Spells |

| 3 | 1004 | Pippin | Fireworks |

Now let’s load the external dataset containing additional information about the fellowship members:

# Load the external dataset

df_external = pd.read_csv("./datasets/LOTR 2.csv")

print(f"Dataset shape: {df_external.shape}")

print(f"Columns: {list(df_external.columns)}\n")

df_external.head()Dataset shape: (5, 3)

Columns: ['FellowshipID', 'FirstName', 'Age']

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | 50 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | 39 |

| 2 | 1006 | Legolas | 2931 |

| 3 | 1007 | Elrond | 6520 |

| 4 | 1008 | Barromir | 51 |

Observation: Both datasets contain information about fellowship members, but they may have:

- Common columns that can serve as keys for merging (like

FellowshipIDorName) - Different sets of attributes that complement each other

- Potentially different numbers of rows (not all members may appear in both datasets)

Our goal is to combine these datasets to create a comprehensive view of the fellowship.

17.2.3 Example 1: Basic Merge with Automatic Key Detection

When both DataFrames have columns with the same name, merge() automatically uses them as keys:

# Merge using automatic key detection

df_merged = pd.merge(df_existing, df_external)

print(f"Original datasets: {df_existing.shape} + {df_external.shape}")

print(f"Merged dataset: {df_merged.shape}")

print(f"\nMerged columns: {list(df_merged.columns)}\n")

df_merged.head()Original datasets: (4, 3) + (5, 3)

Merged dataset: (2, 4)

Merged columns: ['FellowshipID', 'FirstName', 'Skills', 'Age']

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | 50 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | 39 |

Alternative Syntax: You can also use the DataFrame method, which is more readable in method chains:

# Using DataFrame.merge() method (equivalent to above)

df_merged_method = df_existing.merge(df_external)

print(f"Results are identical: {df_merged.equals(df_merged_method)}")

print(f"Merged dataset shape: {df_merged_method.shape}\n")

df_merged_method.head()Results are identical: True

Merged dataset shape: (2, 4)

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | 50 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | 39 |

17.2.4 Example 2: Merging with Different Column Names

What if the key columns have different names in each DataFrame? Use the left_on and right_on parameters to specify which columns to match.

# Example: Suppose the external dataset uses 'ID' instead of 'FellowshipID'

# Let's create a version with a different column name to demonstrate

df_external_renamed = df_external.rename(columns={'FellowshipID': 'ID'})

print("External dataset columns after renaming:")

print(list(df_external_renamed.columns))

print()

# Now merge using left_on and right_on

df_merged_diff = pd.merge(

df_existing,

df_external_renamed,

left_on='FellowshipID', # Column name in left DataFrame

right_on='ID' # Column name in right DataFrame

)

print(f"Merged dataset shape: {df_merged_diff.shape}")

print(f"Merged columns: {list(df_merged_diff.columns)}\n")

df_merged_diff.head()Important observations:

- Notice that both key columns (

FellowshipIDandID) appear in the result - They contain identical values (the matched keys)

- You can drop one of them after merging:

df_merged_diff.drop('ID', axis=1)

Common use case: Merging data from different sources where column naming conventions differ (e.g., customer_id vs cust_id, date vs timestamp).

17.2.5 Example 3: Merging on Multiple Columns

Sometimes you need to match rows based on multiple columns together (composite keys). This is common when a single column isn’t unique.

# Example: Merge on both Name AND Race to ensure exact matches

df_multi_key = pd.merge(

df_existing,

df_external,

on=['Name', 'Race'] # Both columns must match

)

print(f"Merged on multiple keys: {df_multi_key.shape}")

print("\nMerging on multiple columns ensures rows match on ALL specified keys\n")

df_multi_key.head()Real-world examples of composite keys:

- Sales transactions: Match on both

Store_IDANDDate(same store can have sales on different dates) - Student grades: Match on

Student_IDANDCourse_ID(same student takes multiple courses) - Time series data: Match on

LocationANDTimestamp(multiple locations measured over time)

Syntax variations:

# Using on= (when column names are the same)

pd.merge(df1, df2, on=['col1', 'col2'])

# Using left_on= and right_on= (when column names differ)

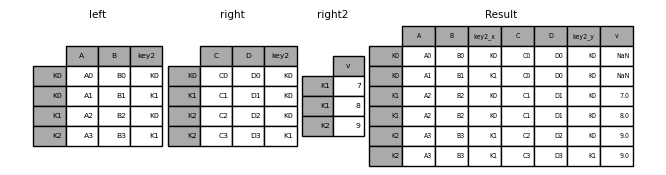

pd.merge(df1, df2, left_on=['id', 'date'], right_on=['ID', 'timestamp'])17.2.6 Understanding Join Types: The how Parameter

By default, merge() performs an inner join, which keeps only rows where the key exists in both DataFrames. However, you can control this behavior using the how parameter.

The Four Join Types:

| Join Type | how= |

Keeps Rows From | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inner | 'inner' |

Both (intersection) | Only matching records |

| Left | 'left' |

All from left + matches from right | Keep all primary data |

| Right | 'right' |

All from right + matches from left | Keep all secondary data |

| Outer | 'outer' |

Both (union) | Keep everything |

Let’s explore each type with examples.

17.2.6.1 Inner Join (Default): Only Matching Rows

An inner join returns only the rows where the key exists in both DataFrames. This is the default behavior.

# Inner join - explicitly specified (same as default)

df_inner = pd.merge(df_existing, df_external, how='inner')

print(f"Inner join result: {df_inner.shape}")

print("Only rows with matching keys in BOTH datasets are kept\n")

df_inner.head()Inner join result: (2, 4)

Only rows with matching keys in BOTH datasets are kept

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | 50 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | 39 |

When to use inner join:

Use inner join when you need complete information from both datasets for your analysis.

Real-world examples:

Analyzing vaccination impact on COVID infection rates

- Dataset 1: COVID infection rates by country

- Dataset 2: Vaccination counts by country

- Why inner join? You can’t analyze the relationship unless you have BOTH metrics for a country. Countries missing either value can’t contribute to the analysis.

Customer purchase analysis

- Dataset 1: Customer demographics

- Dataset 2: Purchase transactions

- Why inner join? To analyze how demographics relate to purchases, you need both demographic info AND purchase history.

A/B testing results

- Dataset 1: User group assignments (control/treatment)

- Dataset 2: Conversion outcomes

- Why inner join? Only users with both group assignment AND outcome data can be included in the test analysis.

17.2.6.2 Left Join: Keep All Left DataFrame Rows

A left join returns all rows from the left DataFrame and matching rows from the right DataFrame. Non-matching rows from the right will have NaN values.

# Left join - keep all rows from left (existing) dataset

df_left = pd.merge(df_existing, df_external, how='left')

print(f"Left DataFrame shape: {df_existing.shape}")

print(f"Right DataFrame shape: {df_external.shape}")

print(f"Left join result: {df_left.shape}")

print("\nAll rows from LEFT dataset are kept, even if no match in RIGHT\n")

# Show rows with missing values from the right dataset

missing_count = df_left.isnull().any(axis=1).sum()

print(f"Rows with NaN values (no match in right dataset): {missing_count}\n")

df_left.head(10)Left DataFrame shape: (4, 3)

Right DataFrame shape: (5, 3)

Left join result: (4, 4)

All rows from LEFT dataset are kept, even if no match in RIGHT

Rows with NaN values (no match in right dataset): 2

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | 50.0 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | 39.0 |

| 2 | 1003 | Gandalf | Spells | NaN |

| 3 | 1004 | Pippin | Fireworks | NaN |

When to use left join:

Use left join when the left dataset contains your primary data that must be retained, while the right dataset provides supplementary information that may be missing for some records.

Real-world examples:

COVID infection rates + government effectiveness scores

- Left: COVID infection rates (critical, hard to impute)

- Right: Government effectiveness scores (can be estimated from GDP, crime rate, etc.)

- Why left join? Keep all countries with infection rate data. Missing government scores can be imputed later using correlated variables.

Customer demographics + credit card spending

- Left: Customer demographics (all customers)

- Right: Credit card transactions (only customers who made purchases)

- Why left join? Keep all customers, even those with no purchases. Missing spend can be filled with 0 (indicating no transactions).

Employee records + performance reviews

- Left: All employee records

- Right: Recent performance reviews (not all employees reviewed yet)

- Why left join? Maintain complete employee roster. Missing reviews can be handled separately (e.g.,

Pending

status).

Key principle: Use left join when you can’t afford to lose the left dataset’s records, and missing right-side values can be reasonably handled (imputed, filled with defaults, or marked as missing).

17.2.6.3 Right Join: Keep All Right DataFrame Rows

A right join is the mirror image of a left join—it returns all rows from the right DataFrame and matching rows from the left DataFrame.

# Right join - keep all rows from right (external) dataset

df_right = pd.merge(df_existing, df_external, how='right')

print(f"Left DataFrame shape: {df_existing.shape}")

print(f"Right DataFrame shape: {df_external.shape}")

print(f"Right join result: {df_right.shape}")

print("\nAll rows from RIGHT dataset are kept, even if no match in LEFT\n")

df_right.head()Left DataFrame shape: (4, 3)

Right DataFrame shape: (5, 3)

Right join result: (5, 4)

All rows from RIGHT dataset are kept, even if no match in LEFT

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | 50 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | 39 |

| 2 | 1006 | Legolas | NaN | 2931 |

| 3 | 1007 | Elrond | NaN | 6520 |

| 4 | 1008 | Barromir | NaN | 51 |

When to use right join:

Right join serves the same purpose as left join, just with the DataFrames swapped. In practice:

- Most analysts prefer left join because it’s more intuitive (reads left-to-right)

- Right join is rarely used - you can always swap the DataFrames and use left join instead

Example equivalence:

# These produce the same result:

df_right = pd.merge(df_A, df_B, how='right') # Right join

df_left = pd.merge(df_B, df_A, how='left') # Equivalent left joinWhen you might see right join:

- Legacy code or specific coding style preferences

- SQL background where RIGHT JOIN might be more familiar

- Method chaining where the order is determined by workflow

Best practice: Stick with left join and arrange your DataFrames accordingly—it makes code more readable and maintainable.

17.2.6.4 Outer Join: Keep All Rows from Both DataFrames

An outer join (also called a full outer join) returns all rows from both DataFrames, with NaN values where matches don’t exist. This is the most inclusive join type—no data is lost.

# Outer join - keep all rows from BOTH datasets

df_outer = pd.merge(df_existing, df_external, how='outer')

print(f"Left DataFrame shape: {df_existing.shape}")

print(f"Right DataFrame shape: {df_external.shape}")

print(f"Outer join result: {df_outer.shape}")

print("\nAll rows from BOTH datasets are kept, with NaN for non-matches\n")

# Check for missing values

print("Missing values per column:")

print(df_outer.isnull().sum())

print()

df_outerLeft DataFrame shape: (4, 3)

Right DataFrame shape: (5, 3)

Outer join result: (7, 4)

All rows from BOTH datasets are kept, with NaN for non-matches

Missing values per column:

FellowshipID 0

FirstName 0

Skills 3

Age 2

dtype: int64

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | 50.0 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | 39.0 |

| 2 | 1003 | Gandalf | Spells | NaN |

| 3 | 1004 | Pippin | Fireworks | NaN |

| 4 | 1006 | Legolas | NaN | 2931.0 |

| 5 | 1007 | Elrond | NaN | 6520.0 |

| 6 | 1008 | Barromir | NaN | 51.0 |

When to use outer join:

Use outer join when you cannot afford to lose any data from either dataset, even if it means having incomplete records.

Real-world examples:

Course surveys from multiple time points

- Dataset 1: Mid-semester survey responses

- Dataset 2: End-of-semester survey responses

- Why outer join? Students who responded to either survey provide valuable feedback. Keep all responses, even from students who only completed one survey. Analyze response patterns and sentiment across all participants.

Multi-source customer data integration

- Dataset 1: Online purchase records

- Dataset 2: In-store purchase records

- Why outer join? Customers may shop through one channel only. Keep all customers to understand total customer base and channel preferences.

Scientific study with partial data

- Dataset 1: Lab test results

- Dataset 2: Clinical observations

- Why outer join? Some subjects may have only lab results or only clinical observations due to scheduling, dropouts, or data collection issues. Keep all subjects to maximize sample size and identify patterns in data availability.

Data quality auditing

- Dataset 1: Expected records (should exist)

- Dataset 2: Actual records (what we have)

- Why outer join? Identify both missing expected records (in left but not right) and unexpected extra records (in right but not left) for data quality assessment.

Key principle: Use outer join when completeness trumps having matched pairs, and you’ll handle missing values appropriately in subsequent analysis.

17.3 Method 2: Joining with join()

While merge() combines DataFrames based on column values, the join() method combines them based on their indices. This is particularly useful when your DataFrames are already indexed by a meaningful key (like customer ID, timestamp, etc.).

17.3.1 Key Difference: merge() vs join()

| Aspect | merge() |

join() |

|---|---|---|

| Joins on | Column values | Index values |

| Default join | Inner | Left |

| Syntax | More explicit | More concise |

| Use when | Keys are in columns | Keys are in index |

17.3.2 Important: Handling Overlapping Columns

Unlike merge(), join() requires you to specify suffixes for overlapping column names (it has no default). This is done with the lsuffix and rsuffix parameters.

Let’s see what happens without suffixes:

The code above will raise an error because both DataFrames have overlapping column names, and join() doesn’t know how to handle them without suffixes.

Let’s fix this by adding suffixes:

# Join with suffixes to handle overlapping column names

df_joined = df_existing.join(

df_external,

lsuffix='_existing', # Suffix for left DataFrame columns

rsuffix='_external' # Suffix for right DataFrame columns

)

print(f"Joined dataset shape: {df_joined.shape}")

print(f"\nColumns with suffixes:")

print([col for col in df_joined.columns if '_existing' in col or '_external' in col])

print()

df_joined.head()Joined dataset shape: (4, 6)

Columns with suffixes:

['FellowshipID_existing', 'FirstName_existing', 'FellowshipID_external', 'FirstName_external']

| FellowshipID_existing | FirstName_existing | Skills | FellowshipID_external | FirstName_external | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | 1001 | Frodo | 50 |

| 1 | 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | 1002 | Samwise | 39 |

| 2 | 1003 | Gandalf | Spells | 1006 | Legolas | 2931 |

| 3 | 1004 | Pippin | Fireworks | 1007 | Elrond | 6520 |

Key Observations:

- Default behavior:

join()performs a left join by default (keeps all rows from the left DataFrame) - Index-based: Rows are matched using the DataFrame indices (0, 1, 2, …)

- Suffixes required: Overlapping column names get the specified suffixes

This works, but notice we’re joining on the default integer index (0, 1, 2, …), which may not be meaningful. Let’s make this more useful by setting a proper index.

17.3.3 Setting a Meaningful Index for Joining

For join() to be truly useful, we should set a meaningful column as the index (like FellowshipID). This way, rows are matched based on actual business logic, not arbitrary row numbers.

# Set 'FellowshipID' as the index for both DataFrames

df_existing_indexed = df_existing.set_index('FellowshipID')

df_external_indexed = df_external.set_index('FellowshipID')

print("Left DataFrame (indexed by Fellowship ID):")

print(df_existing_indexed.head())

print("\nRight DataFrame (indexed by FellowshipID):")

print(df_external_indexed.head())Left DataFrame (indexed by Fellowship ID):

FirstName Skills

FellowshipID

1001 Frodo Hiding

1002 Samwise Gardening

1003 Gandalf Spells

1004 Pippin Fireworks

Right DataFrame (indexed by FellowshipID):

FirstName Age

FellowshipID

1001 Frodo 50

1002 Samwise 39

1006 Legolas 2931

1007 Elrond 6520

1008 Barromir 51# Now join using the FellowshipID index

df_joined_indexed = df_existing_indexed.join(

df_external_indexed,

lsuffix='_existing',

rsuffix='_external'

)

print(f"Joined dataset shape: {df_joined_indexed.shape}")

print(f"\nIndex name: {df_joined_indexed.index.name}")

print("\nNow rows are matched by FellowshipID, not arbitrary row numbers!\n")

df_joined_indexedJoined dataset shape: (4, 4)

Index name: FellowshipID

Now rows are matched by FellowshipID, not arbitrary row numbers!

| FirstName_existing | Skills | FirstName_external | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FellowshipID | ||||

| 1001 | Frodo | Hiding | Frodo | 50.0 |

| 1002 | Samwise | Gardening | Samwise | 39.0 |

| 1003 | Gandalf | Spells | NaN | NaN |

| 1004 | Pippin | Fireworks | NaN | NaN |

Perfect! Now the join is meaningful:

- Rows are matched by

FellowshipID(a business key) - All rows from the left DataFrame are kept (default left join)

NaNvalues appear whereFellowshipIDdoesn’t exist in the right DataFrame- The index preserves the key for easy lookup

17.3.4 Changing Join Type in join()

Just like merge(), you can specify the join type using the how parameter:

# Examples of different join types with join()

print("Inner join:")

print(df_existing_indexed.join(df_external_indexed, how='inner', lsuffix='_L', rsuffix='_R').shape)

print("\nOuter join:")

print(df_existing_indexed.join(df_external_indexed, how='outer', lsuffix='_L', rsuffix='_R').shape)

print("\nRight join:")

print(df_existing_indexed.join(df_external_indexed, how='right', lsuffix='_L', rsuffix='_R').shape)Inner join:

(2, 4)

Outer join:

(7, 4)

Right join:

(5, 4)17.4 Method 3: Concatenating with concat()

While merge() and join() combine DataFrames by matching keys or indices, concat() simply stacks DataFrames together either vertically (one on top of another) or horizontally (side by side). Think of it as physically gluing DataFrames together.

17.4.1 The Two Directions: axis Parameter

axis= |

Direction | Effect | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (default) | Vertical | Rows on top of rows | Combining data from multiple time periods |

| 1 | Horizontal | Columns side by side | Adding new features/attributes |

17.4.2 Concatenating Along Rows (Vertical Stacking)

The default behavior (axis=0) stacks DataFrames vertically—adding more rows.

17.4.2.1 Simple Example with Fellowship Data

Let’s start with a simple example using our LOTR datasets to understand the basics:

# Split our LOTR data into two groups to demonstrate concatenation

lotr_df1 = df_existing.head(5) # First 5 fellowship members

lotr_df2 = df_existing.tail(4) # Last 4 fellowship members

print("First group:")

print(lotr_df1)

print("\nSecond group:")

print(lotr_df2)# Concatenate vertically (default: axis=0) - stack rows

lotr_combined = pd.concat([lotr_df1, lotr_df2])

print(f"First group: {lotr_df1.shape}")

print(f"Second group: {lotr_df2.shape}")

print(f"Combined: {lotr_combined.shape}")

print("\nRows are simply stacked on top of each other:\n")

lotr_combinedKey points about vertical concatenation:

- Rows are simply stacked (group 1 rows, then group 2 rows)

- Index values may be duplicated (notice indices 0-4 appear, then 5-8)

- All columns from both DataFrames are kept

- No key matching occurs—just physical stacking

Use ignore_index=True to create a new sequential index:

# Reset index to create sequential numbering

lotr_combined_reset = pd.concat([lotr_df1, lotr_df2], ignore_index=True)

print("With ignore_index=True, we get a clean sequential index:\n")

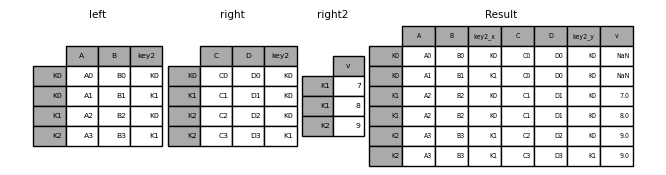

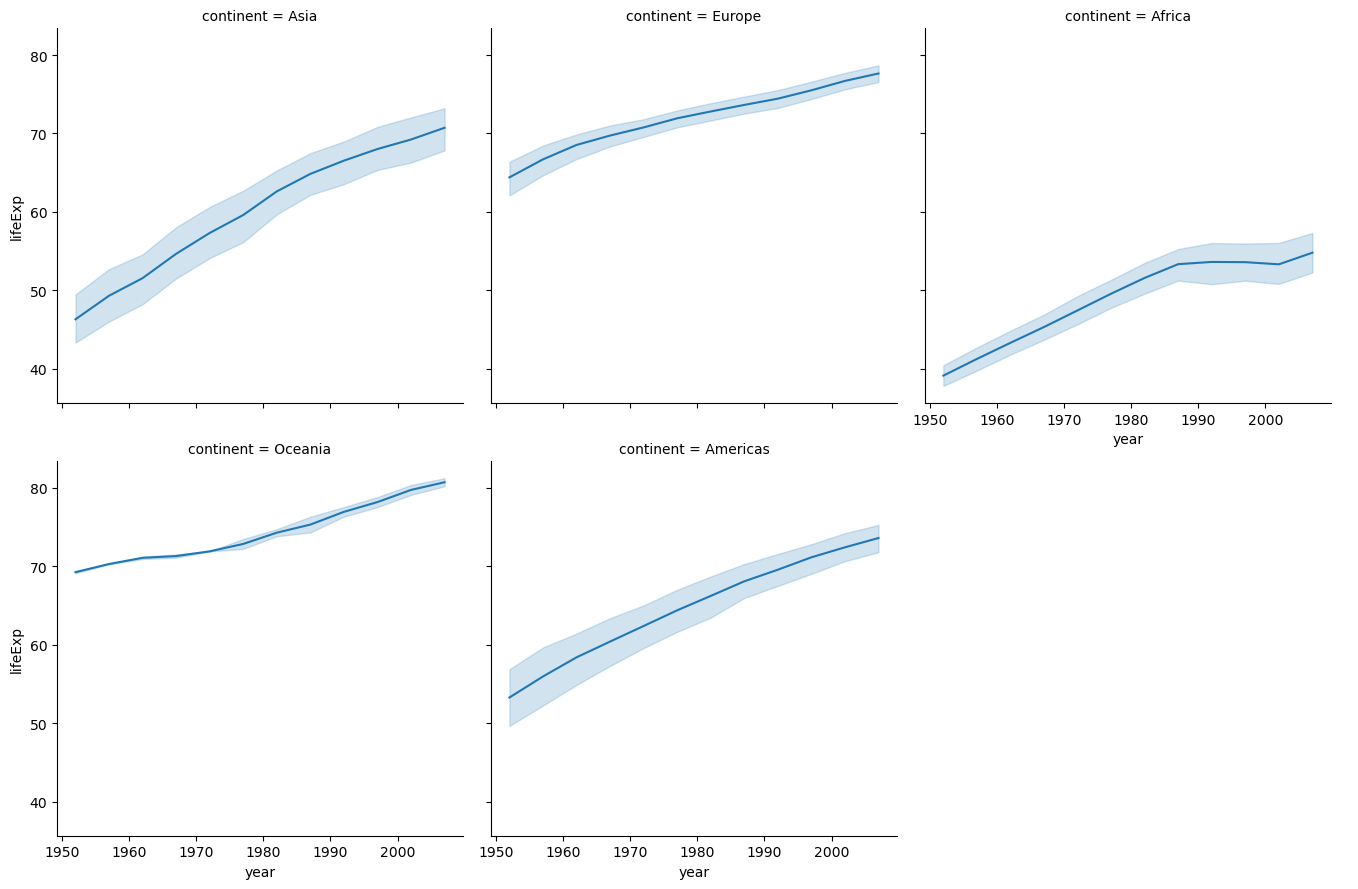

lotr_combined_reset17.4.2.2 Real-World Example: Combining Continental Data

Now let’s see a practical real-world use case: combining GDP and life expectancy data that’s been split across multiple files by continent. This is a common scenario when data is stored in separate files for organizational purposes.

data_asia = pd.read_csv('./Datasets/gdp_lifeExpec_Asia.csv')

data_europe = pd.read_csv('./Datasets/gdp_lifeExpec_Europe.csv')

data_africa = pd.read_csv('./Datasets/gdp_lifeExpec_Africa.csv')

data_oceania = pd.read_csv('./Datasets/gdp_lifeExpec_Oceania.csv')

data_americas = pd.read_csv('./Datasets/gdp_lifeExpec_Americas.csv')#Appending all the data files, i.e., stacking them on top of each other

data_all_continents = pd.concat([data_asia,data_europe,data_africa,data_oceania,data_americas],keys = ['Asia','Europe','Africa','Oceania','Americas'])

data_all_continents| country | year | lifeExp | pop | gdpPercap | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 0 | Afghanistan | 1952 | 28.801 | 8425333 | 779.445314 |

| 1 | Afghanistan | 1957 | 30.332 | 9240934 | 820.853030 | |

| 2 | Afghanistan | 1962 | 31.997 | 10267083 | 853.100710 | |

| 3 | Afghanistan | 1967 | 34.020 | 11537966 | 836.197138 | |

| 4 | Afghanistan | 1972 | 36.088 | 13079460 | 739.981106 | |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Americas | 295 | Venezuela | 1987 | 70.190 | 17910182 | 9883.584648 |

| 296 | Venezuela | 1992 | 71.150 | 20265563 | 10733.926310 | |

| 297 | Venezuela | 1997 | 72.146 | 22374398 | 10165.495180 | |

| 298 | Venezuela | 2002 | 72.766 | 24287670 | 8605.047831 | |

| 299 | Venezuela | 2007 | 73.747 | 26084662 | 11415.805690 |

1704 rows × 5 columns

Let’s have the continent as a column as we need to use that in the visualization.

data_all_continents.reset_index(inplace = True)

data_all_continents.head()| level_0 | level_1 | country | year | lifeExp | pop | gdpPercap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Asia | 0 | Afghanistan | 1952 | 28.801 | 8425333 | 779.445314 |

| 1 | Asia | 1 | Afghanistan | 1957 | 30.332 | 9240934 | 820.853030 |

| 2 | Asia | 2 | Afghanistan | 1962 | 31.997 | 10267083 | 853.100710 |

| 3 | Asia | 3 | Afghanistan | 1967 | 34.020 | 11537966 | 836.197138 |

| 4 | Asia | 4 | Afghanistan | 1972 | 36.088 | 13079460 | 739.981106 |

data_all_continents.drop(columns = 'level_1',inplace = True)

data_all_continents.rename(columns = {'level_0':'continent'},inplace = True)

data_all_continents.head()| continent | country | year | lifeExp | pop | gdpPercap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Asia | Afghanistan | 1952 | 28.801 | 8425333 | 779.445314 |

| 1 | Asia | Afghanistan | 1957 | 30.332 | 9240934 | 820.853030 |

| 2 | Asia | Afghanistan | 1962 | 31.997 | 10267083 | 853.100710 |

| 3 | Asia | Afghanistan | 1967 | 34.020 | 11537966 | 836.197138 |

| 4 | Asia | Afghanistan | 1972 | 36.088 | 13079460 | 739.981106 |

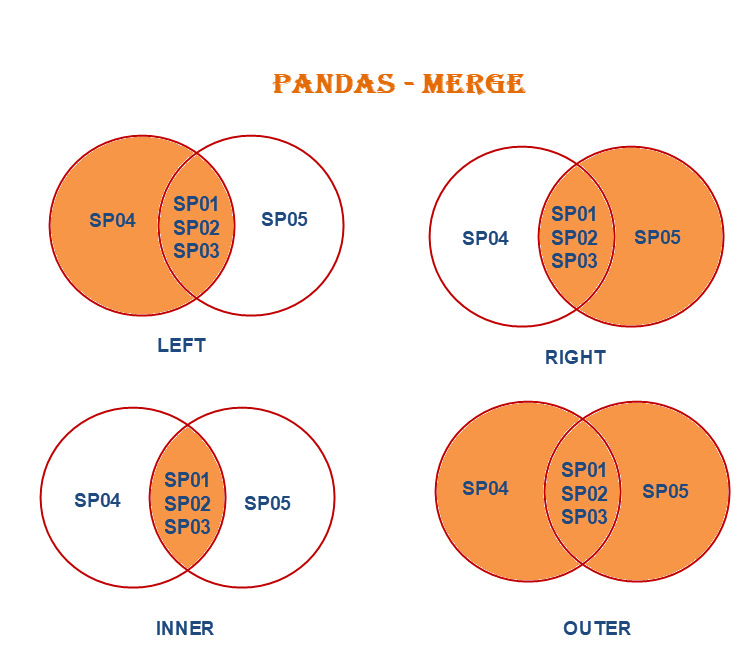

#change of life expectancy over time for different continents

a = sns.FacetGrid(data_all_continents,col = 'continent',col_wrap = 3,height = 4.5,aspect = 1)#height = 3,aspect = 0.8)

a.map(sns.lineplot,'year','lifeExp')

a.add_legend();

In the above example, datasets were appended (or stacked on top of each other).

Datasets can also be concatenated side-by-side (by providing the argument axis = 1 with the concat() function) as we saw with the merge function.

17.4.3 Horizontal Concatenation (Combining Columns)

Setting axis=1 combines DataFrames side-by-side by aligning their indices.

# Concatenate horizontally (axis=1) - combine columns

result = pd.concat([df_existing, df_external], axis=1)

result| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | FellowshipID | FirstName | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1001.0 | Frodo | Hiding | 1001 | Frodo | 50 |

| 1 | 1002.0 | Samwise | Gardening | 1002 | Samwise | 39 |

| 2 | 1003.0 | Gandalf | Spells | 1006 | Legolas | 2931 |

| 3 | 1004.0 | Pippin | Fireworks | 1007 | Elrond | 6520 |

| 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 1008 | Barromir | 51 |

Notice:

- DataFrames are placed side-by-side

- Index values are used for alignment (matching FellowshipIDs are aligned)

- Non-matching indices result in NaN values

- This is similar to an outer join on the index

When to use horizontal concat:

- Adding new features/columns to existing data

- Combining results from different analyses on the same observations

- Building feature matrices for machine learning (each DataFrame contains different feature sets)

17.4.3.1 Handling Duplicate Column Names

When concatenating horizontally with duplicate column names, pandas keeps both columns:

# See column names when both DataFrames have 'Name'

result.columnsIndex(['FellowshipID', 'FirstName', 'Skills', 'FellowshipID', 'FirstName',

'Age'],

dtype='object')Both Name columns are kept, which can be confusing. You can use the keys parameter to create hierarchical column names:

# Use keys to label which DataFrame each column came from

result_labeled = pd.concat([df_existing, df_external], axis=1, keys=['Fellowship', 'Extended'])

result_labeled| Fellowship | Extended | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FellowshipID | FirstName | Skills | FellowshipID | FirstName | Age | |

| 0 | 1001.0 | Frodo | Hiding | 1001 | Frodo | 50 |

| 1 | 1002.0 | Samwise | Gardening | 1002 | Samwise | 39 |

| 2 | 1003.0 | Gandalf | Spells | 1006 | Legolas | 2931 |

| 3 | 1004.0 | Pippin | Fireworks | 1007 | Elrond | 6520 |

| 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 1008 | Barromir | 51 |

Now you can clearly see which DataFrame each column came from. This creates a MultiIndex for columns (we’ll cover this in detail in future chapters).

17.5 Summary: Choosing the Right Method

Now that we’ve covered all three methods for combining DataFrames, here’s how to choose:

| Method | Best For | Key Feature | Common Pitfall |

|---|---|---|---|

merge() |

Combining on shared column(s) | Flexible join types (inner/left/right/outer) | Forgetting to specify join type (defaults to inner) |

join() |

Combining on index values | Quick syntax for index-based joins | Index must be set up properly beforehand |

concat() |

Stacking DataFrames with same structure | Simple vertical/horizontal stacking | Doesn’t match on keys (just stacks/aligns) |

17.5.1 Decision Tree:

Do you need to match rows based on values in columns?

- Yes → Use

merge()(specify join type andon=parameter)

- Yes → Use

Do you need to match rows based on index values?

- Yes → Use

join()(ensure indices are meaningful)

- Yes → Use

Do you just need to stack DataFrames?

- Vertically (add more rows) → Use

concat(axis=0) - Horizontally (add more columns) → Use

concat(axis=1)(aligns on index)

- Vertically (add more rows) → Use

17.6 Handling Missing Values After Combining Datasets

When you combine datasets using merge(), join(), or concat(), you often introduce missing values (NaN) for unmatched entries. Understanding why these appear and how to handle them is crucial for maintaining data quality.

17.6.1 Why Missing Values Occur

Missing values appear for different reasons depending on the join type:

| Join Type | When NaN Appears | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Left Join | Right DataFrame has no match for left keys | Customer exists but has no purchases → purchase columns = NaN |

| Right Join | Left DataFrame has no match for right keys | Purchase exists but customer deleted → customer columns = NaN |

| Outer Join | Either DataFrame has no match | Missing data from both sides |

| concat (axis=1) | Indices don’t align | Different row indices → NaN where no alignment |

Inner joins never produce NaN from the join operation itself (only matched rows are kept).

17.6.2 Strategies for Handling Missing Values

The right strategy depends on why the data is missing and what you’re analyzing.

17.6.2.1 Strategy 1: Keep the Missing Values

When to use: Missing values are meaningful and represent absence

of something.

Example: Customer purchase analysis with left join

# All customers + their purchases (if any)

df_customer_purchases = customers.merge(purchases, on='CustomerID', how='left')Interpretation:

- NaN in purchase columns = Customer hasn’t made a purchase yet

- This is informative - these customers might be new or inactive

- Analysis:

What percentage of customers have never purchased?

requires keeping NaN

Action: Keep NaN and analyze it as a category (e.g., df['Purchase'].isna().sum())

17.6.2.2 Strategy 2: Fill with Default Values

When to use: Missing values should be interpreted as zero or a default state.

Example: Sales data where no transaction = zero sales

# Fill missing sales with 0

df_merged['TotalSales'] = df_merged['TotalSales'].fillna(0)

df_merged['TransactionCount'] = df_merged['TransactionCount'].fillna(0)Common fill values:

0- for counts, amounts, quantities'None'or'Unknown'- for categorical dataFalse- for boolean flags- Mean/median - for numerical features (use with caution!)

Caution: Only fill when you’re certain what the missing value means.

17.6.2.3 Strategy 3: Drop Rows with Missing Values

When to use: Analysis requires complete information from both datasets.

Example: Analyzing relationship between two variables (need both)

# Drop rows where either GDP or Population is missing

df_complete = df_merged.dropna(subset=['GDP', 'Population'])Options:

dropna()- drop rows with any NaNdropna(subset=['col1', 'col2'])- drop only if specific columns have NaNdropna(thresh=5)- drop only if fewer than 5 non-NaN values

Caution: You’re losing data! Document how many rows were dropped and why.

17.6.2.4 Strategy 4: Use a Different Join Type

When to use: You’re getting NaN because you used the wrong join type!

Example: Used outer join but only need matching rows

# Wrong: Creates many NaN values

df_outer = pd.merge(df1, df2, how='outer') # 1000 rows, 50% NaN

# Better: Use inner join to keep only complete matches

df_inner = pd.merge(df1, df2, how='inner') # 600 rows, 0% NaNBefore handling missing values, ask: 1. Did I use the right join type for my analysis question? 2. Should I actually be using inner join instead of left/outer? 3. Are the missing values telling me about data quality issues?

17.6.3 Practical Example: Handling Missing Values

Let’s see these strategies in action with our fellowship data:

# Create an outer join to see missing values

df_outer_example = pd.merge(df_existing, df_external, how='outer')

print("Outer join result:")

print(f"Total rows: {len(df_outer_example)}")

print(f"\nMissing values per column:")

print(df_outer_example.isnull().sum())

print(f"\nRows with ANY missing value: {df_outer_example.isnull().any(axis=1).sum()}")

df_outer_exampleNow let’s apply different strategies:

# Strategy 1: Identify WHERE the missing values are

print("Rows with missing 'Race' (from left dataset):")

print(df_outer_example[df_outer_example['Race'].isna()][['Name', 'Race', 'Birthplace']])

print()

print("Rows with missing 'Birthplace' (from right dataset):")

print(df_outer_example[df_outer_example['Birthplace'].isna()][['Name', 'Race', 'Birthplace']])# Strategy 2: Drop incomplete rows (for complete-case analysis)

df_complete = df_outer_example.dropna()

print(f"Original rows: {len(df_outer_example)}")

print(f"Complete rows: {len(df_complete)}")

print(f"Rows dropped: {len(df_outer_example) - len(df_complete)}")

print()

df_complete# Strategy 3: Fill with meaningful defaults

df_filled = df_outer_example.copy()

df_filled['Birthplace'] = df_filled['Birthplace'].fillna('Unknown')

print("After filling missing 'Birthplace' with 'Unknown':")

print(df_filled[['Name', 'Birthplace']])

print(f"\nMissing 'Birthplace' values: {df_filled['Birthplace'].isna().sum()}")17.6.4 Best Practices for Missing Value Handling

1. Investigate First

# Always check WHERE and WHY values are missing

df.isnull().sum() # Count per column

df[df['column'].isna()] # See the actual rows2. Document Your Decisions

# Good: Document what you did and why

# Filled missing GDP with 0 because these are countries with no economic data reported

df['GDP'] = df['GDP'].fillna(0)

# Also good: Create a flag for missing values before filling

df['GDP_was_missing'] = df['GDP'].isna()

df['GDP'] = df['GDP'].fillna(df['GDP'].median())3. Consider the Impact

- Dropping rows: Reduces sample size, may introduce bias

- Filling with defaults: May distort statistics (mean, correlations)

- Keeping NaN: Requires careful handling in analysis/visualization

4. Choose Join Type Carefully

The best way to handle missing values is often to prevent them by using the right join type for your analysis question!

Remember: Missing values after combining datasets are expected and normal. The key is understanding what they mean and handling them appropriately for your specific analysis goals.

17.7 Independent Study

17.7.1 Merging GDP per capita and population datasets

In this independent study on data reshaping, we have provided two datasets:

- gdp_per_capita_data

- population_data

This exercise builds on the results from the previous section.

Task:

Merge gdp_per_capita_data with population_data to combine each country’s population and GDP per capita into a single DataFrame.

Finally, print the first two rows of the merged DataFrame.

Assume that:

We want to keep the GDP per capita of all countries in the merged dataset, even if their population in unavailable in the population dataset. For countries whose population in unavailable, their

Populationcolumn will showNA.We want to discard an observation of a country if its GDP per capita is unavailable.

17.7.1.1

For how many countries in gdp_per_capita_data does the population seem to be unavailable in population_data? Note that you don’t need to clean country names any further than cleaned by the functions provided.

Print the observations of gdp_per_capita_data with missing Population.

17.7.2 Merging datasets with similar values in the key column

We suspect that population of more countries may be available in population_data. However, due to unclean country names, the observations could not merge. For example, the country Guinea Bissau is mentioned as GuineaBissau in gdp_per_capita_data and Guinea-Bissau in population_data. To resolve this issue, we’ll use a different approach to merge datasts. We’ll merge the population of a country to an observation in the GDP per capita dataset, whose name in population_data is the most similar

to the name of the country in gdp_per_capita_data.

17.7.2.1

Proceed as follows:

For each country in

gdp_per_capita_data, find thecountrywith the mostsimilar

name inpopulation_data, based on the similarity score. Use the lambda function provided below to compute the similarity score between two strings (The higher the score, the more similar are the strings. The similarity score is \(1.0\) if two strings are exactly the same).Merge the population of the most

similar

country to the country ingdp_per_capita_data. The merged dataset must include 5 columns - the country name as it appears ingdp_per_capita_data, the GDP per capita, the country name of the mostsimilar

country as it appears inpopulation_data, the population of that country, and the similarity score between the country names.After creating the merged dataset, print the rows of the dataset that have similarity scores less than 1.

Use the function below to compute the similarity score between the Country names of the two datasets:

from difflib import SequenceMatcher

similar = lambda a,b: SequenceMatcher(None, a, b).ratio()

Note: You may use one for loop only for this particular question. However, it would be perfect if don’t use a for loop

Hint:

Define a function that computes the index of the observation having the most

similar

country name inpopulation_datafor an observation ingdp_per_capita_data. The function returns a Series consisting of the mostsimilar

country name, its population, and its similarity score (This function can be written with only one line in its body, excluding the return statement and the definition statement. However, you may use as many lines as you wish).Apply the function on the

Countrycolumn ofgdp_per_capita_data. A DataFrame will be obtained.Concatenate the DataFrame obtained in (2) with

gdp_per_capita_datawith the pandasconcat()function.

17.7.2.2

In the dataset obtained in the previous question, for all observations where similarity score is less than 0.8, replace the population with Nan.

Print the observations of the dataset having missing values of population.